Welcome back, or just welcome if it’s your first time here! Today we’re continuing our worldbuilding process series by taking a look at language mapping. For the uninitiated, we’ve been creating a series of blog articles detailing steps on worldbuilding a world/setting for D&D and other fantasy TTRPGs, primarily through top-down worldbuilding. You can find all the blog articles and supplemental resources here.

Great, let’s get into it!

What is Language Mapping?

Good question. Veteran world builders are familiar with the “monoculture” cliche. For our fantasy TTRPGs, it means boiling down an entire species (race) to a single, monolithic culture. And I don’t think anything reflects that in D&D quite as much as languages. All civilized people speak “Common,” all goblins speak “goblin,” and many monsters speak a racial language in addition to Common.

It’s a bit silly to think about. Why would an entire band of orc raiders rampaging across the steppe learn Common? How would giants on opposite sides of the world learn to speak the same primary language? Language mapping helps rectify that by creating a literal map of world languages assigned geographically.

Why Do Language Mapping?

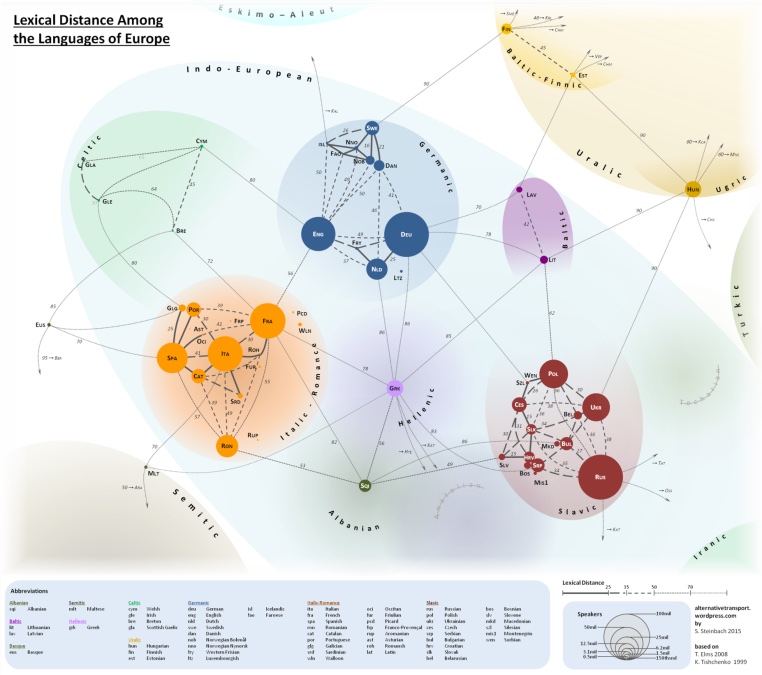

Two reasons; the first is verisimilitude. For example, in D&D 5e, there are 16 core languages, eight standard and eight exotic. And most of the exotic languages are planar in origin, not terrestrial. Contrast that to the real world, where the eighth most spoken language is Russian, and the 16th is Telugu (India). Our total estimated number of languages on Earth is 6500-7200.

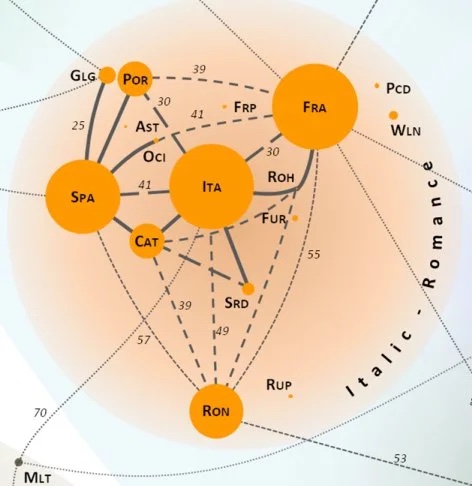

Now, are we going to make thousands of conlangs? No. What we want to do is reinforce that the further we move away from a point in the world, the more different languages become (lexical distance). As a real-world example, let’s use Italy as a starting point. Using the image below, we can see that French, Spanish, Sardinian, and Catalan are similar.

So using some pidgin, it’s reasonable that you can read and communicate more effectively than, say, an English speaker as English is lexically only one pitstop away but in an entirely different language group.

This mapping is also useful as the Romance languages have a common progenitor in Latin. It may be a dead language, but we seem to gravitate towards it in pop culture for important, ancient, and magical/mystical uses. As are other languages, like Gaelic.

Improving Worldbuilding Immersion

That could be a very important point for games set in your fantasy world, which brings us to the second reason: immersion. Healthily borne from my own bias, I know. Still, language is really important for a game that has an entire third of its core gameplay pillars focused on social interaction and has multiple magic spells specifically for communicating with other creatures.

Consider how important language, or more specifically, the inability to communicate efficiently is to entertainment media. In James Clavell’s Shogun, the main character is an English pilot (sailor) shipwrecked in Japan, where he has to slowly self-teach himself the language through the novel so he can communicate with the Japanese. The plot of the highly-regarded Arrival (2016) sci-fi movie revolves around learning an alien language. Or, the importance of Sinric, a recurring wanderer and polyglot in the Vikings tv show that serves as a guide, interpreter, and bargaining chip between the Franks and Vikings during the third season.

Our games can take on a completely different feel if the party travels across the material plane and beyond, but they cannot rely on Common to talk with every creature and society. Suddenly, they will need to rely on interpreter NPCs with their own agendas and allegiances or burn spell slots or coins purchasing scrolls to gain the ability to communicate magically.

Or, consider the Latin example from above. What if the party’s barbarian character is critical to deciphering an ancient magical inscription in a dungeon simply because the barbarian speaks the most lexically similar language? Now it’s a team effort between the barbarian and Arcana-trained PCs to translate and decipher (imperfectly) the meaning of the writing. I like that a lot better than having an investigation/exploration scene where the martial character players have nothing to do since they’re not trained in a requisite skill.

Currently, our group is in the Underdark and needed to communicate with a group of Kua-Toa. Of course, no one in the group speaks Undercommon. That made first impressions tense as we wanted to get information from the group and not fight them. I chalk up the fun and tension of the situation to our DM, a veteran who served in the intelligence arm overseas. He keenly understands the necessity for communication and how difficult it can be when it’s something we take for granted but suddenly can’t rely upon.

Hopefully, that shows how powerful a language mapping tool can be for your worldbuilding. But enough talking about it; let’s map it!

If you like the blog, there’s plenty more where that came from! In addition to the website, we also produce content on Twitch and YouTube. On Twitch, we’re running an ongoing D&D Solo Adventure starring the wizard and disgraced researcher: Lia Amakiir. You can find the backlog of those sessions over on our YouTube channel. But really, I want to point your attention towards our video on 10 Anime Recommendations for D&D Fans!

Creating Language Groups

We briefly touched on language groups, but it’s worth discussing a bit more thoroughly. As you might guess, they’re groups of lexically similar languages. The Italo-Romance languages we used in the Italy example are one such group. Now, in the world I’m creating, I decided to draw from existing real-world examples of language groupings primarily because I don’t have the desire to construct brand new languages and the whole want to avoid languages based on species/race.

Here are the language groups I included in my language mapping:

- Altaic

- Austro-Asian

- Celtic

- East Asian

- Germanic

- Greek

- Indian

- Inuit

- Iranian

- Niger-Congo

- North American Indian

- Romance

- Slavic

- South American Indian

Far from an accurate depiction of the roughly 7,000 languages we have on Earth, but it must suffice. You may notice that these groups are quite Western-Europe-centric. I scoured for more sources on different global language groups but couldn’t find much usable material. Just to say, it wasn’t my attention but rather a lack of readily-available source material I could find. Same for the names of the language groupings.

I’m sure someone with a strong linguistics or constructed language background would be able to make something more diverse and intelligible.

If so, please do it and share. We desperately need it!

Mapping Languages to the World

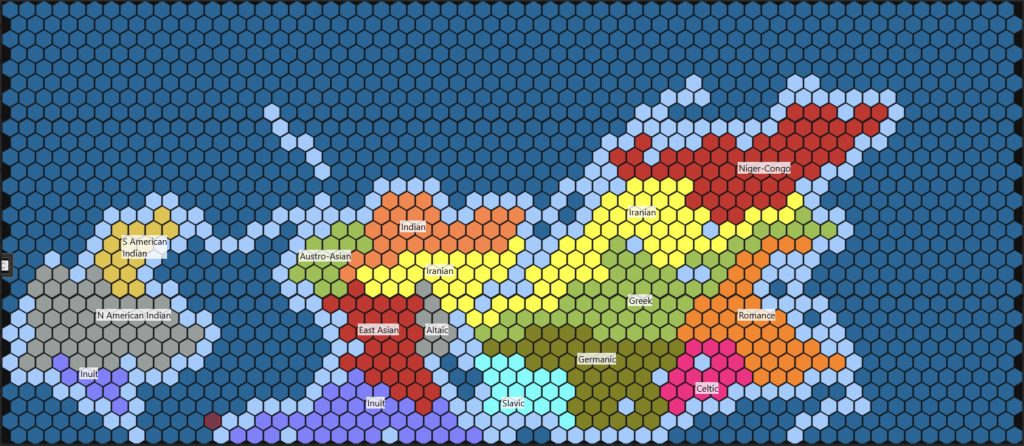

I will go ahead and drop in the completed map of world languages so we can reference it as we walk through the process.

When placing languages on the map, we want to emphasize creating language “borders” that make sense. For instance, the South American language group is quite lexically distant from the Romance language group. Therefore on the map, you’ll see they are literally a world apart, separated by an ocean and most other language groups.

Now, thanks to the lack of non-European language information, there will be times when you won’t have a good sense of the linguistic distance between two or more language groups. Or at least that was the case for me. In those instances, I substituted real-world geographic distance, and I think it worked as well as could be expected.

However, you do have to be careful not to get tripped up. For instance, a significant portion of Portuguese (Romance) speakers are in Brazil. So there can be geographically close languages that are not organically (lexically) similar. Thanks for making this process just a little more difficult imperialism! So be cautious of any bloc of European-origin language speakers outside of Europe when making this substitution.

Now, that said, people do migrate and bring their language with them. Using the previous example, we can absolutely have Romance language group speakers on the Western continent. If anything, that’s quite likely due to sea travel and trade in the world. But those speakers will be very much in the minority unless you’re modeling imperialism in your worldbuilding.

And that’s not the only potential reason languages travel. In the map above, you can see that our Inuit language group is on two continents, bordering both North American Indian and East Asian language groups. I did this to model the Bering Land Bridge theory. If you don’t know, the theory posits that ancient man crossed from NE Asia to North America by foot during the ice age when the Bering Strait was frozen. This decision also aligns with my headcanon for the history of that part of the world. I don’t believe I’ve shared it yet, and I’m not going to. It still needs to percolate before being presented. Sorry!

Biome Synergy in Language Mapping

Another consideration I kept in mind during the mapping process was an attempt to create synergy between the placement of the language groups and the world map’s biomes because language is a product of its people and environment, such as the old chestnut, about 50 words for snow in Eskimo. That’s not exactly true, but cold climate words and ideas are indeed emergent in Inuit languages.

And if I placed those languages in the middle of a tropical jungle biome, I’d be atrophying keystones of the language group. Similarly, language groups may not have native words for jungle or rainforest, instead using loanwords to describe non-native environments and concepts. That muddies the water of what we’re trying to accomplish with this exercise.

Also important is a consideration for your players or audience. Fiction and TTRPGs heavily rely on archetypes, stereotypes, and collective assumptions as building blocks for exploring fantasy and science fiction themes. For example, when I say dwarf or elf in a fantasy TTRPG context, we conjure a similar image and understanding of what that represents. This construct is good, it’s shorthand to help people understand the surface level of your world so they can spend their mental efforts diving deep.

So, expectations are good, and so are subverting those expectations. But you must be careful because subversion works best when it’s a flavoring, a spice that complements the meal. Use too much, and you’ll ruin the meal, try to serve herbs and spices as a meal by itself, and no one will want to partake. If I’d slapped the Slavic group down in the Chaparral/Mediterranean biome in my map, it would likely be more confusing for my players than fun.

I can imagine trying to put on a Russian accent for an NPC, and my players forget they’re in a sun-soaked scrubland or assume the NPC wasn’t native to the area due to the accent. Which… is silly to think about as Slavs (ethnolinguistic group) absolutely migrated into the biome.

You’re Not Going to Have a Perfect Map of World Languages

Like a lot of worldbuilding, it can be difficult to leave well enough alone. For success, it’s essential to understand that you won’t get it perfect. Heck, I don’t even know what perfect would look like on my map. Depending on the constraints of your map and the lexical distance of the languages/groups you’re trying to assign, there probably isn’t a singular perfect interpretation.

For Instance, I did a little micro worldbuilding for a game I was running in this world we’ve been building, and I needed to place the Celtic language group in a specific area because I already used it in that worldbuilding. It’s not in the ideal spot on the map, but we do as we can to get things down on paper and keep the worldbuilding momentum going. It can be highly alluring to waste a lot of time wrapped up in chasing the perfect language map.

Spending time on minute details isn’t by itself bad. If you’re worldbuilding simply as a fun exercise, then by all means, have at it! But, my worldbuilding efforts, and most people’s, are in service of some other goal. Worldbuilding goals, like running a D&D campaign, create a purpose that your worldbuilding serves.

And that’s not to say this section or any part of worldbuilding has to be perfect on the first pass. Unless you’re under a publishing deadline, this is all for fun for yourself and to share with friends. If you discover you majorly screwed something up later, you can always retroactively fix or redact it.

I think I’ll follow my own advice and wrap this blog up before I go down another few thousand words of a rabbit hole. Instead, I’ll save that info for our next blog!

Map of World Languages

In this blog, we discussed language mapping and its usefulness for worldbuilding, especially in breaking up the D&D trope of species/racial languages. We discussed language groupings and how to apply those groupings to your world map in a thoughtful manner.

The next worldbuilding process series blogs, I think, will focus on how to use the map of world languages as a worldbuilding tool and kick off the long-awaited conversation of worldbuilding cultures and adding them to our setting!

If you enjoyed this content, don’t forget we do more than the blog! Check out the RedRaggedFiend YouTube Channel and subscribe for more advice and actual plays. If you want to see the Solo RPG adventures as they happen or want to be part of the conversation in these videos, follow the RedRaggedFiend Twitch channel!

This blog and the rest of RRF content is a personal labor of love. If you’d like to support the creation of more, you can do that in three easy ways. You can support the blog for free by sharing this content on social media, Reddit, and your favorite TTRPG forums. If you’re in a position to support the content financially, you can Donate Through Ko-Fi, and pick up one or more of our Pay-What-You-Want resources on DriveThruRPG!

And that’s going to be it for me. Thanks for reading, and I’ll see you next time!

This is a great post! I’m currently working on a D&D campaign setting!

Thanks, glad you found it helpful!

And how would dialects play into this? Would a goblin tribe from the north speak the same Goblin dialect as a tribe from the south? There are literally hundreds of intelligent monsters in D&D not counting the extra-planar. Which is an opportunity to really expand the language map. Would an Abyssal on the upper crust of the Nine Hells speak the same dialect as an a demon from the 125th layer of The Abyss?

In this particular world example I’m dropping the idea of race/species-specific languages. Certainly there are plenty of smaller dialects.

I toyed with the idea of having percentile rolls for communicating through different dialects but I suspect that crosses the threshold where realism in the game makes it less fun to play!