One of the most common questions from DMs of all stripes, especially new DMs and soon-to-be DMs, is how do I prepare for D&D sessions? And I thought now is a good time to kick it around and look at how I’ve been preparing for sessions lately. I want to preface here that we’re discussing session prep, not prepping/creating an adventure. I have a post about making adventure outlines, campaign starts, and dungeons that you can take review if that’s what you need.

Since we’re prepping a session, I expect you have a basic skeleton outline of your adventure already planned and in process. This outline could be a published module, a dungeon outline, or a homebrew adventure outline. Where session prep comes to fruition is by filling in the flesh around the outline of your adventure.

If you’re not that far yet in your D&D prep, see how I improved my homebrew D&D adventures and the updates I’ve made to my adventure outline technique, the adventure skeleton.

So, you have your adventure outline and your next session coming up. Let’s get started.

Start at the End (of the Session)

One of the first secrets of being an effective Dungeon Master is recognizing that prepping can happen while the current session is still going on. That’s why we take notes. The first and perhaps best piece of advice to improve your effectiveness and efficiency in session prep is to force your group to agree on their next course of action at the close of a game session if it’s unclear. Getting a definitive “we are going to X to do Y” tells you as a DM exactly where you need to focus your efforts to prepare for the next game.

Close out your game sessions by asking for feedback. At the end of each session, I ask my players, “Do you have any questions, comments, concerns; things you liked and want more of, things you want to see less of going forward?”

Players won’t give you any meaningful feedback 99.99% of the time, but it’s important we provide them the opportunity to speak up and provide input.

Post-Session Prep

Once everyone leaves, I’ve found this is the best time to write the session recap. Everything is fresh in my mind, and I can bullet point outline everything of note that happened during the session to use at the start of the next game session.

Post-Session Countdowns & Timers

After the recap, I create and modify any live timers/countdowns. These are PC backstory points, unresolved consequences from previous adventuring, and factions in the world making moves to further their goals. I assign each a die size based on how soon I think this should come up, and after each session, I roll the die. On a one, I reduce the size of the die. If I roll a one on a four-sided die, I replace it with a one.

In the next session, I’ll look for an opportunity to foreshadow this coming up if possible. Then the timer counts down to zero, and consequences show up as soon as the opportunity arises.

Take a Break & Bunk Off

Whether it’s school, work, or D&D, the human brain is great at turning the wheels when we disengage from the task at hand. It allows our brains to basically transfer information from RAM short-term memory to the brain’s HDD for long-term memory.

It’s why we get the great ideas in the shower.

This advice is tough for me in particular because I’m usually champing at the bit after a session to start prepping while my brain is still in D&D mode. But, it can be limiting and tiring forcing your prep for the next session right after the previous session is over.

Instead, make your notes and walk away for a day or so. Let potential ideas simmer on the back burner of your mind for a little while, then come back fresh.

Return to D&D Session Prep

After a day or so to let things percolate in the mind, it’s time to prepare for your next D&D session. The first thing I do is review my notes, expiring timers, and the party’s confirmed course of action to start the next session.

Start Session Prep Reviewing These 3 Points

- The Party’s Confirmed Course of Action

- Expiring & Foreshadowing Countdown Timers

- Last Session’s DM Notes

These are my foundation for things that might happen in the next session. From there, I start bullet-pointing scenes/encounters.

How Many Encounters to Prep for a D&D Session

Unfortunately, there’s no firm number of scenes or encounters to prep for a D&D session because time is variable and difficult to predict.

On average, for a typical 3-4 hour session with a group of 4-5 players, they average about five scenes/encounters per session.

If you have more players, you’ll need fewer scenes, and vice versa is true. The number of players talking at the table determines how long scenes will last. It’s more rolls, questions, and difficulty confirming a decision or course of action.

However, it still all depends on the type of scene or encounter. Some scenes take only a few minutes, even with a large party of player characters, while some intense scenes alone can run for longer than an hour.

Types of D&D Encounters to Prep

Variety isn’t just the spice of life; it’s one of the keys to keeping your game sessions fun and interesting. I want to avoid a string of the same kinds of encounters. Combat encounters are fun, but three in a row, and the game will drag, and players lose interest. So, we want to use our three pillars of D&D, plus some mixed encounters to keep things even fresher. That gives us six types of encounters/scenes while prepping. That makes it pretty easy to avoid a lot of back-to-back scene styles.

D&D Encounter Types

- Combat

- Exploration or Investigation

- Social Interaction

- Mixed Scenes

- Combat + Exploration/Investigation

- Exploration/Investigation + Social Interaction

- Social Interaction + Combat

Examples of Mixed Scenes

An example of a combat + exploration/investigation scene could be one where the party needs to hold back a wave of enemies while the rogue works on unlocking the door that will lead the party to safety. Another typical combat + exploration scene would be a chase scene.

An example of an exploration/investigation + social interaction encounter would be a “one of us always lies, one of us always tells the truth” riddle. Other examples include an encoded message or other puzzles where part of overcoming the challenge is successfully using social interaction.

Social interaction + combat scenes can include a hostage situation, underworld exchange, or combat game/sport. They can be tense situations that can slide in and out of physical violence or fun encounters where showmanship is just as important as technical combat prowess to putting on a good show.

DM Tip: Don’t Force Encounter Types

We want to provide obstacles and opportunities to our players, not locks that only have one key. Players are unpredictable, you may have a combat encounter lined up only for the players to decide they want to parley, trick the baddies, or sneak around them. If it’s a reasonable means of bypassing the obstacle, let them do it.

The Hiccup Method

Sometimes, when running a game, you need to add some cushion for pacing. Controlling the pace of your game is especially important when you want to find a good spot to end the next session on a cliffhanger. Try the hiccup method if you need to add some more scenes for your next session. All you need to do is look at your bullet points of potential scenes and think about what could present itself as an obstacle between each scene.

Wandering monsters, hazards, and complex traps often serve as suitable “hiccups” to create space between your scenes/encounters. It can be as simple as a door being stuck or barred from the other side, a classic spiral staircase slide trap, or a nasty hazard like Memory Moss that can force the party to adjust to a new situation before proceeding.

DM TIP: Hiccup Adventure & Campaign Prep

You can actually use this exercise to prep an entire adventure or campaign. Create a starting point, an endpoint, and then continue creating potential obstacles and challenges between them as nodes.

Over-using the hiccup method can burn out players to the point where they feel like even the simplest tasks feel overly complicated to achieve. You’ve probably experienced this in video games, especially poorly made side quests, when you feel like there are too many steps to completing a relatively simple objective. Fetch and delivery are the primary offenders. Don’t lean too heavily on the Hiccup Method.

Another thing to include in your prep that can help spread things out while potentially adding depth to your game is prepping inter-scene moments or fluff.

Prepare Inter-scene Moments & Fluff

These are similar to Mike “Sly Flourish” Shae’s Secrets & Clues step included in the excellent, Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master. It’s a dumping ground for things you want to add to your D&D sessions that aren’t enough to build an entire scene around, or pieces of quest-relevant information or worldbuilding/setting information you want to share with the players by showing, not telling.

Other instances of moments and fluff would be fostering natural Role-play moments, very minor random “encounters,” or introducing a non-sequitur to raise the eyebrow of your players. Moments & fluff can also be used as narrative cues to include foreshadowing, hints at future plot setups, talk about a PC’s backstory, and transition fodder between established scenes. Another use is to gift your players something new or interesting for them to find.

Here are some inter-scene moments & fluff I had prepped for a recent D&D session

- NPC A gets sidetracked investigating and sketching an ancient dwarvish device

- A distant, bellowing roar echoes up the corridor from somewhere within the complex (Foreshadow Troll Encounter, Expiring Timer)

- NPC B pulls one of the PCs aside to air concerns about the “Dead Weight” in the adventuring band

- You come across a rat that appears to apprise you intelligently and will scurry, then stop, attempting to lead you elsewhere?

- NPC C gains a head-splitting headache (Save vs. Enthrall, SUCCESS, Foreshadow Aboleth BBEG)

- In an alcove stands a pedestal topped by a bull-headed stone idol. Carved into its open hands is an offering plate, still stained by its ancient, rotted away offerings

- Beneath a loose floor tile, you find the rotted remains of a coin purse with 2d6 ancient coins (Successful Investigation/Trap Check)

Once you have a list prepared, look for moments where the players are just moving down a corridor, struggling with what to do next, or resting. Injecting these moments between your scenes provides an experience outside the typical Kill, Find, and Talk encounters that comprise the meat of a D&D session. Inter-scene moments & fluff can make players feel like you’ve done far more meticulous session prep than you truly have.

At the end of your session, you can scratch out the ones you used and any bullets that would no longer make sense. For instance, in my notes, if the party decided to leave the current dungeon, I’d strike the dungeon-specific bullets and replace them with moments that make more sense for the environment they’re in now.

So you may wonder how many of these bullets you should prep for a game session. Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master advises ten. In the example above, I have seven. Realistically, in the average game session, I’d find an opportunity to use half of them. Because, to me, these are filler, and they shouldn’t pull the focus and momentum of the session. My only exception would be if I wanted to pace the session’s run time for a good stopping point.

Preparing D&D Encounter/Scene Information

D&D session prep methods are like fingerprint sets, and each DM is unique. That being the case, I can’t tell you something that will 100% work for you. What I can do is talk about what’s worked for me over the years.

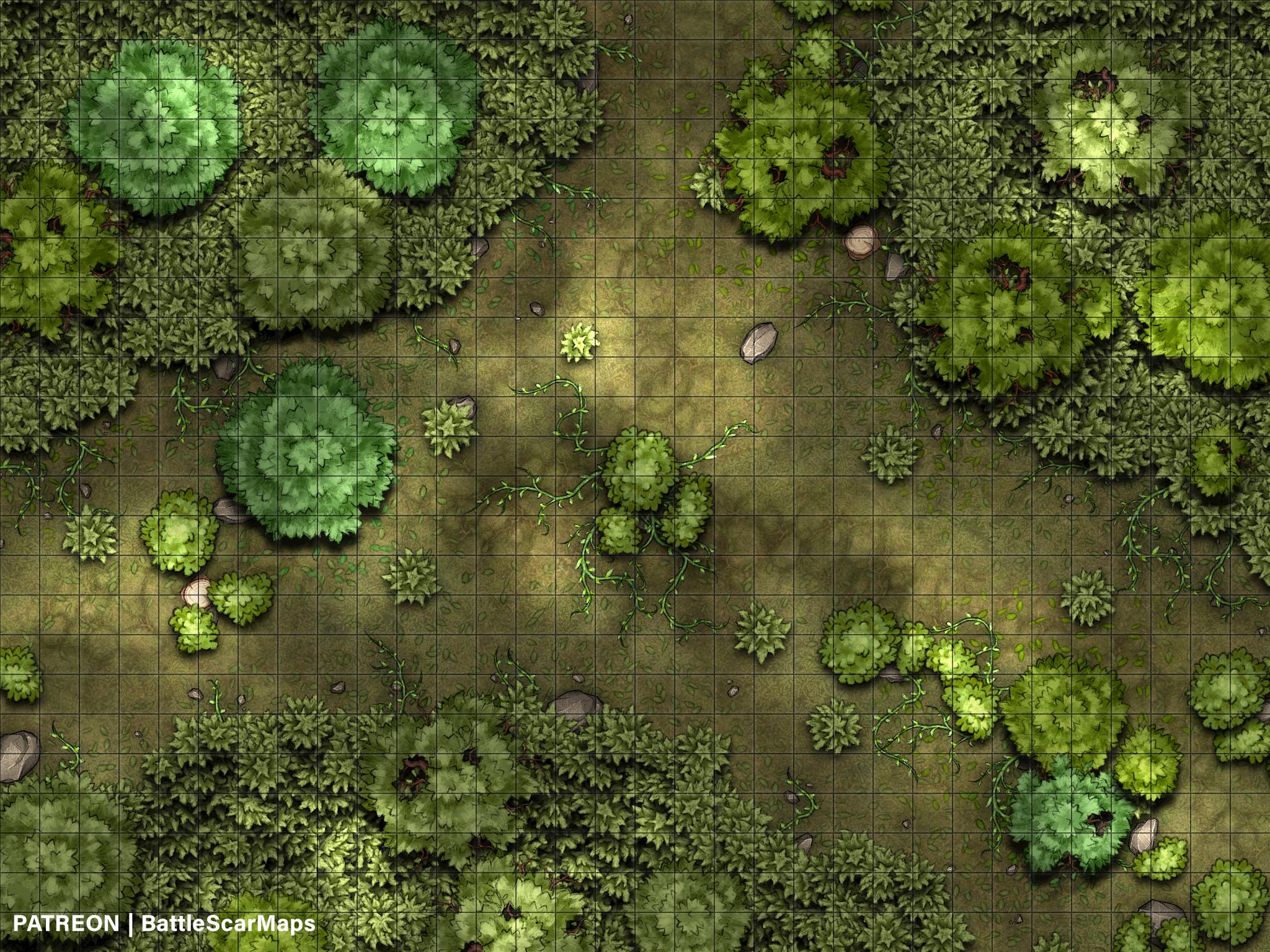

I think many DMs, including myself, start with the visuals of a scene. This visual could be finding a suitable battle map or evocative backdrop image to present during scenes.

One Dungeon Master I met online uses pictures on a virtual tabletop as background images. They even use a tavern scenes, placing PC and relevant NPC tokens on the heads of the people in the scene to provide context for the players. It helps to give a sense of space when we’re not physically sitting next to each other.

In my case, I’ve embraced theater-of-the-mind style play for the past few years. Fifth edition is well-suited for it compared to D&D 3.0-4 and Pathfinder 1-2, where specific, tactical positioning is essential in combat. For the most part, I don’t use many visuals when I play, instead leaning into my verbal description of scenery, creatures, and actions. The tradeoff is I’m more flexible and pointed about understanding what a player is trying to do, and I spend a little extra time reiterating where things are in relation to the PCs.

Depending on the adventure in my session prep, I often need to either expand the description of the scene or reduce it. The latter is usually in adventure modules where I need to compress lengthy block text to its most salient points. And in the former’s case, I may have just a few notes about a dungeon chamber, like its size, shape, purpose, and a detail like it’s suffering from water damage.

Below I have some tips that will help you describe scenes like an absolute master of dungeons!

D&D Scene Prep Step One

Lean into your group’s shared understanding of archetypes and tropes. We probably don’t need to explain how a mead hall looks to fantasy RPG players. Even if the exact same vision doesn’t spring to mind, your players understand the archetype of a mead hall and what would be in it.

It probably has long tables, benches, casks, empty tankards/drinking horns, a long trench in the center for fire and light, and a raised seat/table for the jarl in residence. It’s probably dark and dingy and probably doesn’t smell fresh.

Step Two

I snuck this in at the end of Step One!

Try to include one non-visual sense in your description of a scene. Smells and sounds are the most common but don’t forget about touch. Remember that touch includes things like airflow, temperature, and humidity.

If your party has been delving a dungeon in the frozen wastes and suddenly reach a chamber with air that feels balmy and humid, their danger sense will start going off.

DM Tip: More Senses Aren’t Better

Some advice tells DM’s to engage all five sense in a scene’s description. But, that bloats scene description and actually dilutes the focus on what’s actually important in the location you’re describing. Really two, maybe three, of the most powerful sensations is what you need. You can (and should) add more sensory detail when your players INTERACT with the scene. How disturbed dust causes the characters to cough as they root through the old desk, etc.

Step Three

Create a focal detail for the scene. And pick something weird or fantastic that reinforces the tone of your game. Let’s go back to the mead hall from Step One. If the monster Grendel’s severed arm is nailed to the cross beam at the center of our mead hall, dripping dark ichor on the floor, that’s a strong tone.

The theme of that mead hall is very different from one that’s washed in cheery, warm light and filled with the smell of spiced pig roasting over the fire.

Bonus Step 3.5

One misstep I’ve made plenty of times and seen from other DMs is not prepping something for the scene’s focal detail. If you put a bloody severed arm in the middle of a room, you need to be prepared for your players to investigate it.

RPGs are different from writing a story. Not every focal point needs to be a plot-critical Chekhov’s Gun, but if it’s important enough to draw attention (doing its job as a focal point), as a Dungeon Masters, we need to be able to sate their curiosity. Roasting pig probably not significant to the adventure, displaying a freshly severed monster arm I would hope so!

Once I’m finished with any descriptive notes about the scene’s setting, I focus on the interactive parts of the scene. Here I’ll note any knowledge or skill checks that I think are relative to the scene. I’ll also include the mechanics of any trips, traps, hazards, and obstacles in the scene the party will likely encounter.

DM TIP: Single Room Check DCs

One of the many cool streamlined ideas from Runehammer and his Index Card RPG is the advice of creating a single Difficulty Challenge or Target Number for each scene. A single number that covers everything the players want to do in the scene. With a +/- modifier (+/-5 is good for D&D 5e) if it seems significantly easier or harder than the room’s DC.

Then I’ll add some notes about any critical creatures to the scenes. These could be NPCs with any necessary description, motivations, and talking points. I follow a similar template with monsters in the scene and include things such as what they’re doing when first encountered, a reaction roll for the situation, and any tactics they might employ in a fight.

Sometimes these notes can be elementary. For example, a dungeon chamber could include these notes:

- Contains broken furniture with the remains of a fire at its center

- Wis/Survival DC 12, fire coals are slightly warm (used in the past 12-24 hours)

- One exit, reinforced door barred from the opposite side, DC 14

- East, Corridor to Room 13 (Kitchen)

- 4 Skeletons (MM272)

- Idle, Passive Perception 9

- No tactics/survival instinct, attacks nearest target

- Will not leave the area

Other rooms with puzzles, complex environmental hazards/traps, or intelligent monsters may require more in-depth notes. In these sections, like most prep, you want to write down any mechanics or details that we’re not 100% sure you’ll remember.

Adjusting Your D&D Session Prep for Player Limelight Moments

With your scenes and inter-scene moments jotted down, take a moment to cross-reference them with your players’ characters. Does each have a moment where the session can focus on them? A cleric PC can step into the skeleton chamber from above and drastically change the encounter’s script with Turn Undead.

These moments don’t necessarily need to tie to the PC’s ABCs (Ancestry, Background, Class). Looking back at the inter-scene moment examples above, I might tie NPC B’s moment to a member of the adventuring party who doesn’t already have a limelight moment. NPC B could as easily approach a barbarian with this issue because the character seems the strongest or the party’s bard because they seem the most approachable.

If none of your scenes, encounters, or inter-scene moments feel like they would highlight a specific player character, create something that will and add or swap it out with something in your notes. It could be a cryptic half a note about a ritual for the wizard to decipher or a rare mushroom with improved anti-toxin properties (removes Poison condition) the Ranger can identify.

Another way to do this is to add some points to your upcoming session that target a particular player’s archetype (actor, explorer, slayer, etc.). Even if their character doesn’t have a limelight moment, players have an opportunity to engage with the aspect of D&D that is the most fun for them. This little detail can help players on opposite ends of the spectrum, such as ensuring there is some opportunity for role play for an actor in a dungeon crawl. You can create a back-alley shakedown or chase scene for slayers in an urban mystery adventure.

Purposeful Start, Write the Lead-In for Your Next Session

Much of the advice for starting a session of D&D revolves around the idea of the “strong start.” Often this is diluted down to starting every session with a combat or other high-energy action scene. But, it gets tiresome to plan and play when every session starts the same. Instead, focus not on a Strong Start but on a Purposeful Start.

A Purposeful Start is not necessarily action, but it gets your players and party quickly moving forward on the plan of action they outlined at the end of the last session. We want to reduce sessions that half-start, stumbling at the beginning. Poor session starts where players continue cross-talk on tangents, hem and haw about what they want to do, and end up deciding to stray from what you prepped after a half hour of screwing around.

To me, this is the fountainhead of each session and serves as a barometer for how sessions typically go. In my experience, this is where games are the most likely to get off track, where players are muddy about what they’re doing, leading to them abandoning the current quest to chase butterflies. Fumbling the start of a session and letting it become an aimless mess off the bat often snowballs into additional issues throughout the session.

So use a Purposeful Start. Write a couple of sentences or bullet points narrating from the end of the session recap to where the action starts. Don’t start by dropping the party into action as they wake up from a rest. Tell them they wake rested, eat, prepare their gear and spells, and pack up. If a nondescript corridor is in front of them, skip that too. Instead, after finishing the session recap, use something like the below example lead-in for the session I’ve described.

“After a long, and luckily uneventful, rest the party strikes camp and moves down the southern corridor. As you reach the end of the corridor, you find your way forward blocked by a door. What would you like to do?”

Occasionally, a player will want to clarify something they did during the rest, or you’ll need to remind them to mark off rations, light a new torch, etc. Still, by writing a lead-in to your next session with purpose, you can avoid the frustration of a game session that goes off half-cocked where the players sit around aimless without knowing what to do.

Extra Credit D&D Session Preparation

Like many experienced Dungeon Masters, I have refined my preferred method of D&D session prep to be quite efficient. It goes by especially quick once I’m in the middle of an adventure or dungeon, and I only need to add or update the information in my session prep that has changed from the last session. That can leave us with time to prepare other things to help us be better DMs and provide a better game session experience for our players; extra credit prep.

Prepare Tools to Improvise

Once you have defined the critical path for your adventure and your next session, you can start painting outside the lines to bring more color to your game. Write some notes about what’s going on nearby. These notes can give you fodder for adventure hooks, things the party can find clues about while out adventuring, and give your local NPCs more tidbits of dialogue to share in interactions with the party.

Prep Drop-in NPCs

Speaking of NPCs, a nice way to prepare yourself for an improvised scene is to make a few general NPCs you can have on hand to slot in when the party decides to throw you a curveball and wants to interrogate the local potter to see if they saw anything while gathering clay from the riverbank.

DM Tip: Index Card NPCs

I like to prep a handful of NPCs with names, physical descriptions, personality traits, items, maybe some skills, tools, or knowledge they can use to assist the party. I put each on an index card and when I need a random NPC, I simply pull one out and use it.

I prefer this method to a random list of names because my experience has been I need maybe two random NPCs in a session. This prep gives me a physical description and personality, which is far more helpful than a hundred names when I only need two, but I still need to invent everything else about the NPCs.

Random Encounter Tables

If I haven’t prepared a random table for the area the party is currently adventuring, I’ll do that here or update the table with new results as needed to keep it fresh. I like a small table, maybe six random encounters based on the party’s current environment. If I use one in a session I mark it out and replace it with a new encounter for future sessions.

Random encounters get a bad wrap, but they’re great when used appropriately. By appropriately, I mean reinforcing the danger of an environment, i.e., the risk of taking a long rest in unsafe areas and introducing action when the players turn indecisive or get stuck.

For more insight on this, I suggest Matt Colville’s Orcs Attack! video

Tiny Loot & Pocket Contents

In addition to random encounters, it’s also nice to prepare some minor treasure parcels.

These are helpful when the players decide to loot a body, you want to reward their curiosity for exploration with a cache of treasure, or whatever improvisation you need to pull off. There are plenty of random treasure generators out there to satiate your need.

I have a random “pocket contents” table with everyday items you might find among someone’s personal possessions. It mainly revolves around EDC (Everyday Carry) items. It’s included in my PWYW Definitive GM Quick Reference for 5e on DriveThruRPG.

Parachute File of One-Shot Adventures

Here’s a prep golden nugget for Dungeon Masters running groups that get sidetracked often.

Spend a lazy afternoon skimming the internet for straightforward adventures that you can drop into your game. Look for one-shot adventures like published play modules, Five Room Dungeons, and one-page adventures. Keep an eye out for adventures that fit the current locale and level of the adventuring party.

The next time your players get off track and stray over the horizon, you can grab a suitable adventure from the file and drop it down in front of them. This little bit of agnostic prep can save you from feeling like you need to prepare everything within travel distance for your next session.

Here are a few of my favorite FREE/PWYW resources for stocking a Parachute File

- Tyler Monahan’s 60 One-Page Adventures

- One Page Dungeon Contest & Compendiums

- 87 5 Room Dungeons

- D&D 5e Adventurers League Adventure Modules

You could run a weekly game for years using these resources without using the same adventure twice. That’s low-cost, high-value DM session prep! Even so, if I have the free time, I occasionally create homebrew adventures for the Parachute File.

For some more advice on creating these simple one-shot style adventures, I suggest looking at the old My Realms Adventure Packets that offer guidance on creating homebrew, one-shot adventures for D&D 4e’s Living Forgotten Realms, the predecessor to 5e’s Adventurers League organized play. It’s a very practical guide for new DMs on how to create and run one shot adventures.

D&D Session Prep: Table Tools

One of the last things you might look at while preparing for your next session of D&D is what tools you want to use at the table.

First, any technology you will want to use while running the game. Having a computer, tablet, or phone at the table can benefit a Dungeon Master. Quick access to monster stat blocks, rules clarifications, and online generators help you improvise, and are all very helpful.

Personally I eschew digital tools for running in-person games, but I often use a mix of digital and analog tools when running games online. I already have a computer in front of me, might as well make the best use of it!

Immersion Tools

Consider what sorts of things you may want to prep to punch up your game to the next level. A session playlist of atmospheric music can be nice. This spot is also where I would look at making any handouts, physical puzzles, ciphers, or other objects for players to interact with at the table.

An inexpensive, tactile puzzle can be a fun way to challenge your players and not their characters in a way that’s unusual in Dungeons & Dragons.

Maps & Miniatures

Unfortunately, my maps and miniatures are gathering dust in the closet. For the past few years, I have been all-in on theater-of-the-mind games. This situation hasn’t been helped by the pandemic’s dissolution of my in-person gaming group during that time. D&D 5e is designed very well to be run as theater of the mind, a significant departure from the previous two iterations of “The World’s Greatest Roleplaying Game.”

But, if you’re playing on a virtual tabletop or an in-person game, you may want to prepare maps and miniature/tokens for your game.

It’s important to be critical of your own DMing style.

In previous sessions, have players often been confused about positioning or the size and layout of areas? Scene and action description may be an underdeveloped area of your Dungeon Mastering. Maps and miniatures make space and positions very clear for everyone at the table. Even a map without miniatures or a picture of a scene as a visual representation can go a long way to ensuring clarity and consensus between you and your players. Plus, fantasy art is really cool and evocative.

The End of Prep: Starting Your Next Session

The start of most successful gaming sessions begins with a recap of the previous session, which you’ve already prepared. One thing I and other DMs like to do is to ask the players to recap the last session. It lets me know what the most memorable parts of the previous session were for my players.

Also, it allows me to make additions and corrections to anything they only half remember. That way my players aren’t operating on misremembered information or an incorrect assumption.

Relax & Have Fun

For me, the start of a D&D session is the most nerve-wracking. Yep, even all these years and games later, I still get nervous running D&D. But, once I get into the session and we enter the D&D cadence of describe, question, and answer, everything is fine.

Try to relax, you have done your preparation, and now your focus should be on creating an entertaining experience for the table.

Even if that means sometimes you need to throw everything you prepped out the window and improvise or pull something from your Parachute File to run.

I’ve found the Dwight E. Eisenhower quote insightful when preparing for games as a Dungeon Master, “plans are useless, but planning is essential.”

The results of session prep isn’t as important as making a point to prepare for your session. Essentially, putting time and effort into thinking about the game your running, what might happen, and how the world might react to player character shenanigans is the point of session prep.

This simple reason is why improv-only game masters will always be inferior in the long run. Yes, they can run an incredibly fun one-shot, but by their nature they are incapable of creating a cohesive D&D campaign/game beyond 2-3 sessions.

Regardless of your masterclass-worthy improv skills and years of experience, always prepare something.

Trust me, a heavily improvised campaign feels as random to your players as it actually is. At the very least, outline the five scenes you expect to happen in the next session.

The Golden Rule of D&D Session Prep

“Prepare everything you’re not comfortable making up on the spot.”

Popularized by Web DM’s Jim Davis, it’s a guiding principle for your game preparation in one statement. New DMs are prone to over preparation because they don’t feel comfortable improvising anything to start. But, with time and experience running game sessions, you will better learn one, how to improvise, and two, what you need to prepare to be comfortable running a session.

For new Dungeon Masters, test yourself to improvise a little each session in different ways. After each session review your prep notes to see what was needed and what wasn’t.

Maybe your players are like mine and seldom ask NPCs for their names, so that big list of names is taking up valuable DM resources space at your table you could allocate to a more useful reference. Over time you will be able to identify the things in your prep that rarely come up in play. Those are things you can cut from your session prep.

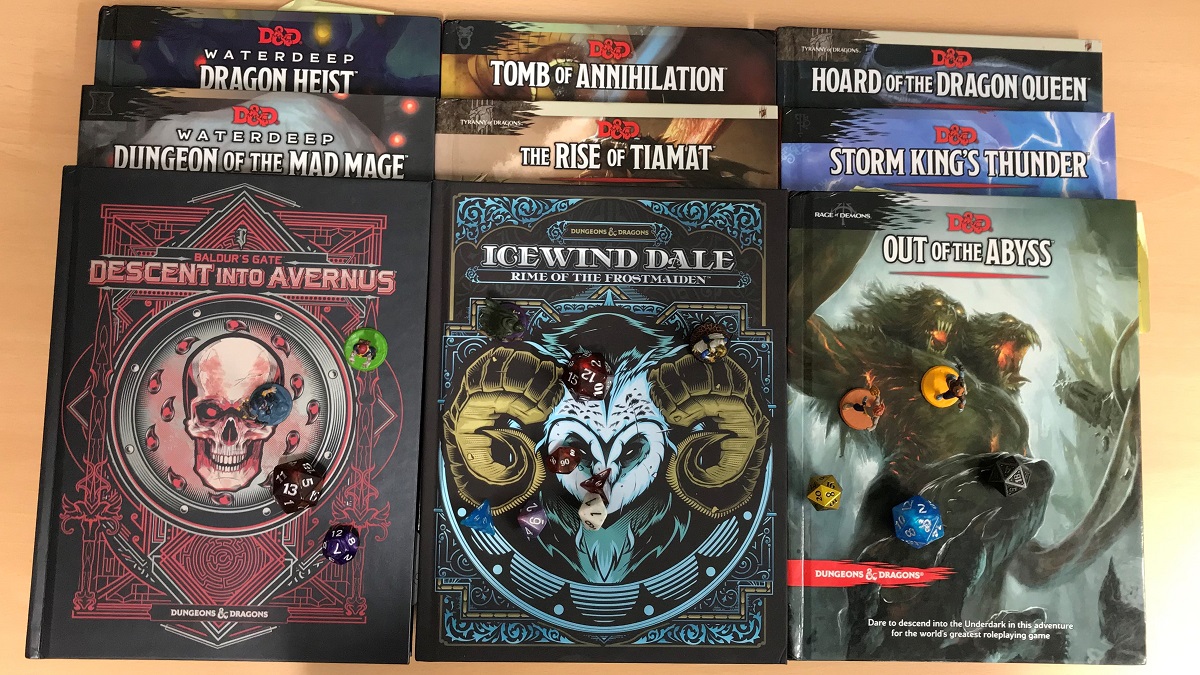

D&D Session Prep for Published Adventure Modules

Everything we’ve spoken about so far has been focused on Dungeon Masters who are making homebrew adventures. But, many DMs are interested in running published adventures, whether they’re short, standalone adventures or hulking, pre-packaged campaigns.

5 Steps to Prepping a Published Adventure

- Before anything, read the adventure (or plot summary + current chapter for an adventure path)

- Read the upcoming 5-7 scenes of the adventure module

- Reread the 5-7 scenes and make notes of the things you don’t think you’ll 100% remember

- If something is unclear or worded strangely, search online and note the clarifications

- Prep the maps, miniatures, stat blocks, and handouts you’ll need for the upcoming scenes

- Add digital bookmarks or sticky flags to a printed book for important details referenced in the scenes that are described elsewhere in the module

- Custom Monster Stats, NPC & Location Info, Treasure, etc.

- Prep some inter-scene moments, random encounters, and parachute file contents to help you improvise and make the adventure your own

The biggest mistake Dungeon Masters make with published adventures is not reading them thoroughly. Yes, that means all the way through, more than once.

I know it’s a pain in the butt, but it’s the tradeoff for not having to come up with the content yourself. You need to download someone else’s adventure plan into your brain to set it as your foundation for running the game.

The nice part is that once you’re familiar with a published adventure, you will feel comfortable adding your own fluff and making tweaks and changes to the adventure to better serve your table and elevate your players’ enjoyment of the adventure.

D&D Session Prep Final Thoughts

There’s no silver bullet when it comes to prep, and just like packing to go on a trip, everybody’s needs are different when it comes to D&D preparation. Struggling with session prep is a normal growing pain experienced by all DMs at some point.

Only by being intentional with your prep and being critical about what is and is not adding to your game experience will help you find your own specific balance of D&D session prep.

Thanks for sticking around to the end, and I hope you found some kernels of valuable tips and wisdom sprinkled throughout that can help you improve your session prep. If you like what we’re doing here, you can help out. We have a Ko-Fi link where you can donate to help support the site. You can also pick up the PWYW titles on DrivethruRPG to support the site while getting something fun.

If you’re short on cash, no worries, you can support the site for free by following and sharing the blog on social media and your favorite RPG subreddit or forum. Every little bit helps. Thanks so much, and let me know on Twitter how you prep for your D&D sessions!