Welcome back to this series on Worldbuilding from scratch. In this installment we’re going to add some variety to our biomes map. If you’ve been following along in the map creation your land masses should have some wide bands of biomes, which is great. However, we want to mottle those bands with some variation to give our maps a little more visual interest and add a degree of believability. We’re going to do that by adding some elevation, adjusting the precipitation and adding in our specialty biome: Wetlands.

Hey, if you’re new or missed the last post about creating your biomes map you can check out the Worldbuilding Process Posts page.

Introduction to Elevation on Your Biomes Map

Elevation is a key component in your biomes map. For biomes, a rise in altitude is similar to the effect of moving an area’s latitude poleward. If you look at a tall mountain range you can see it go through the same biome changes as the elevation increases as would happen if the area was moving away from the equator. At the highest elevations land passed by the tree line: the elevation at which the environment can no longer support tree growth. This is similar to the transition between Taiga and Tundra. The elevation effect is one of the reasons Incan terrace farming was so successful. The Inca could grow a diverse array of crops in close, geographical proximity by planting them higher or lower on terraced mountain slopes.

The first thing we need to do to begin with elevation is define some elevation-related landforms. Unfortunately, the real world doesn’t provide us with any hard and fast rules about delineating the difference between a mountain, a hill, and things like plateaus and highlands. Many hills are larger than the smallest mountain and so on. Therefore, we’re going to make some up for ease of use.

Mountains, 2,000 to 30,000 ft (600 to 9000 m)

These peaked landforms rise 2,000 feet or more above the surrounding land. To keep in line with Earth, the tallest my mountains are allowed to rise are 30,000 feet above sea level. That’s just a little bit taller than Mt. Everest. Depending on a mountain’s height your biomes map may change due to elevation.

Biomes Map Active Mountains vs Inactive Mountains

Mountains created by active plate tectonic activity tend to be taller than inactive mountains. The Himalayas and Andes: active and tall; The Urals and Appalachians: inactive and shorter. To easily randomize the difference in these mountains you can use 2d10 for inactive mountain height and 1d20+1d10 for active mountain height.

Hills < 2,000 ft (< 600 m)

Rounded landforms that rise LESS than 2,000 feet from the surrounding land. This makes it easy for us. Anything over 2,000 feet in elevation change will be a mountain and anything less will be a hill. Alone, hills are not tall enough to cause a change on your biomes map. However, they may breach cause a shift in elevation when combined with highlands/plateaus.

Highlands/Plateau 400 to 17,000 ft (100 to 5200 m)

Highlands, uplands, plateaus, foothills, tablelands, hill countries; whatever your name, are all a contiguous area of raised land. Because highlands are a contiguous area they can also stack with hills and mountains. Your plateau could also have a tall, active mountain range. This is precisely the case with the Tibetan Plateau, home to the Himalayas. As a rule of thumb, highlands rise approximately 400 to 17,000 feet above surrounding land. With such a wide range of elevation it is possible your highlands may not be tall enough to change your biomes map. But, hills and mountains on short highlands are likely to cause a biome shift. Something to consider when creating contiguous areas of higher elevation on your map.

How Elevation Changes Your Biomes Map

A mountain in the 48-54° latitude band of Temperate Forest with a rise of 2500 ft would be treated as if it was at 54-60°, placing it in the Taiga band. Leaving your deciduous forest nestled around a small, pine-covered mountain.

About every 2500 ft of elevation increase shifts biomes on your biomes map six degrees poleward. So if the mountain from before was 5000 ft tall it would move 12 degrees poleward, potentially creating a mountain peak that enters the Tundra latitudes (rises above the treeline). A 30,000 ft mountain on the equator would still be snow capped and considered to be sitting at 72° N/S.

Using this criteria a hill by itself cannot be tall enough to change the region’s biome. But, depending on the rise in elevation highlands, plateaus, and mountains generally do. A hill may cause a change in elevation when placed in the highlands or on a plateau. Something to keep in mind while reviewing your map elevations.

One degree of latitude shift rarely makes a difference for worldbuilding purposes. To the point tracking individual degrees of shift due to elevation would not be a productive use of time and energy on your biomes map. But, if you did want to track it, ~417 ft (~127 m) in elevation changes equals 1° of latitude change.

Biomes Map Mountain Rain Shadows

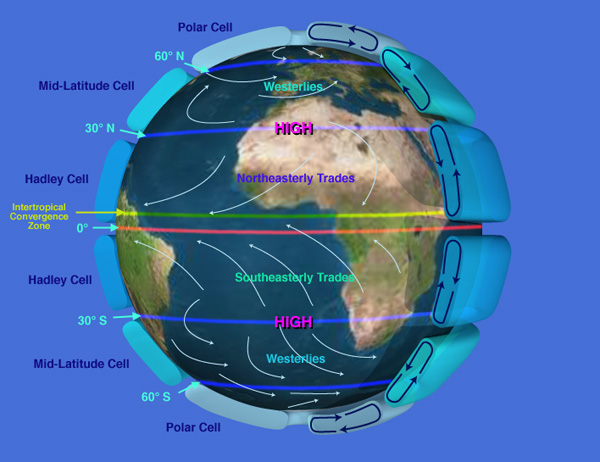

Turn back your minds to the beginning of our mapping adventure and discussion on prevailing winds. See the image if you need a refresher. When winds travel across mountains they have to physically rise in the air to do so. As clouds rise the air gets cooler, moisture condenses, and precipitation falls on the near side of the mountain. The taller the mountains, the more precipitation will be dropped on the near side and less will carry across the ridge line and fall on the lee side.

Tall mountain ranges tend to cause deserts on their lee (far) side. Not so tall mountain ranges affect precipitation on the lee side to a lesser degree. Instead of deserts, your mountains’ lee side will feature more scrub land, grasslands, or in extremely humid latitudes, dry forest.

That’s it for our discussion of elevation. However, there is a type of specialty biome we teased in the last segment. Now, we’ll be looking in detail at wetlands and how they can spice up your map. But, before that I want to give you a nice random roll table to help you easily diversify your biomes map.

2d6 Biomes Map Diversity Roll Table

2 Water1 3 Wetland 4 Verdant (Desert > Plains > Forest > Dense Forest) 5 Verdant (Desert > Plains > Forest > Dense Forest) 6 Unchanged 7 Unchanged 8 Unchanged 9 Drier (Forest > Plains > Desert) 10 Drier (Forest > Plains > Desert) 11 Highlands/Hills2 12 Mountain3 1Note the hex’s original biome (primary land biome when submapping the biomes map's hex) 2If already a Hill, detail combined elevation for a hill on a highland rise 3If already a Mountain, detail combined elevation for a mountain on a highland rise

Wetlands and Worldbuilding

Despite being regularly overlooked in worldbuilding, wetlands are essential to a good biomes map. Because fresh water is life, wetlands are welded to the course of human history. They provide sources of fuel and iron, fertile soil, rich hunting/gathering resources, and are natural defenses against invaders. Plus, they make for great adventure fodder.

There are four kinds of wetlands: bogs, fens, marshes, and swamps. Each is a little different. In the grand scheme of your world map and the stories you will likely tell it doesn’t really matter if you’re 100% accurate. You don’t need to sweat these details, but it is nice to know the difference between the wetland types and people utilize them.

Bogs

Bogs form as precipitation-fed lakes that fill with decomposing material. Your bogs should NOT be connected to surface water like rivers or groundwater like springs and aquifers. Bogs have an acidic pH and are filled with peat. They offer little flora and the soil is not useful for planting crops.

However, bogs ARE prime for fungus, carnivorous plants, and… cranberry cultivation. Humans are mostly interested in bogs for two reasons: peat and bog iron. Peat can be cut and dried to create a useful fuel source. Bog iron is free, impure iron that forms in… bogs. A small, but useful source of iron that is often a side effect of peat cutting and doesn’t require mining.

So, it’s perfectly reasonable people would want to live near and claim ownership over a bog. For your worldbuilding there is one other benefit of bogs: bog bodies. Bogs are really great at mummifying creatures and we have remains of people from as far back as the Mesolithic period. Mummies, disposed murder bodies, fungi, carnivorous plants, and murky water basically writes itself as a fun D&D adventure.

Fens

Fens are quite similar to bogs. The immediate difference is fens are generally fed by groundwater and sometimes surface water. So if you want to throw a spring, aquifer, or stream into a bog-type location it’ll be a fen. Because of the water difference, fens have more flora and less peat than bogs. They have a more Alkaline pH, but still lack suitable soil composition for cultivating crops.

That’s really the big difference between bogs and fens. People will be drawn to fens for the same reasons they’re drawn to bogs, but their results for peat and iron deposits will be less fruitful. Fens do have more biodiversity, making them a great place to drop in a hag, or folk healer that needs very specific plants for very specific rituals, potions, medicines, and the like. Both fens and bogs make good locations for classic D&D monsters like myconids, shambling mounds, and otyughs.

Marshes

Marshes are wetlands that form along the floodplains of rivers and lakes. Due to this, marshes are more prevalent in the middle and lower courses of a river. Don’t worry, we’ll cover more about the courses of a river in the next segment. For now, note marshes are more likely to occur in the lowlands and not the highlands or mountains.

Tall reeds and grasses that often tower over a person’s head dominate marshes and they offer a great amount of biodiversity. Marshes also feature good soil composition. People love marshes and river valley civilizations existed primarily due to marshes and seasonal flooding. Living next to a river, people often drain nearby marshes and use the fertile soil for crops.

Marshes also offer a wide assortment of sea life and fowl to hunt, plus some nasty, riverine animals like hippos, snakes, and crocodiles. If you’ve played Assassin’s Creed Origins, you will be very familiar with marshes.

Marshlands are great fodder for your stories or D&D adventures. Because of the tall grass and reeds, an uncultivated marsh makes it easy for travelers to get lost. While adventurers are unlikely to starve there are many dangers. Animals, insects, parasites, trench foot, inability to find fire fuel or dry ground to rest can be an issue. Meaning even in mild temperatures adventurers could suffer hypothermia. Not to mention the great amount of D&D monsters that inhabit marshes. Toss in a few elementals, some natural beasts, bullywugs, lizardfolk, yuan-ti, and cap it off with a hag or black dragon.

They also provide a strong, natural defense against enemies. The lagoons and marshlands surrounding Venice made it a very difficult city to attack or siege by land. But, the reverse is also true. Because of the maze-like nature, marshes can be great secret bases for bandits, outlaws, and raiders to strike nearby locations. Perfect for replacing a cave for the staple, low-level “clear out the bandits” D&D quest.

Swamps

Swamps are like marshes PLUS. The major difference between the two is the size of the body of water they’re attached to and the primary flora that’s present. Swamps form along large rivers and lakes and are able to sustain the growth of trees, shrubs, and other woody flora. Like marshes, they offer good soil composition and are often drained and cleared by people for farmland. Because people are lazy, given the chance they will cultivate a marsh over cutting down acres of half-submerged trees.

Both swamps and marshes are also capable of forming in coastal, brackish water (where fresh and saltwater mix). When that happens a swamp is often called a mangrove and a marsh is often called a… saltmarsh. Yes, just like the anthology of D&D coastal adventures: Ghosts of Saltmarsh. Not very unique is it?

Which Wetland to Use Where

If you’ve finished fine-tuning your map, we know the largest lakes that show up. Any wetlands next to those big lakes are going to be swamps. Beyond that, it will be difficult to make any decisions about which wetland is where at this point because you don’t know much about the rivers of your world. We’ll resolve that in the next section. Still, I want to finish the explanation of wetlands here.

From how the wetlands form you should have a good idea of where they should be placed in your world. If you have a wetland next to running water you know it won’t be a Bog. A small river isn’t likely to support a swamp. And a waterlogged area surrounded by forest isn’t likely to be a marsh. Fens won’t form next to a substantial river so they’re likely to form along river tributaries in a river’s higher course (again, we’ll discuss this more later). Here’s a quick reference.

Biomes Map Wetlands Quick Reference

River/Lake? Yes Big: Swamp/Mangrove Small: Marsh/Saltmarsh More Stream/Pond: Fen No, Groundwater? Yes: Fen No: Bog

If you’re unsure if it’s a Bog or a Fen, you can use the ambiguous identifier Moor/Moorland. Or, you can call everything a Wetland and be done with it. It’s up to you.

Biomes Map Finishing Touches

Look over your map to correct two common anomalies.

- Make sure your elevations and rain shadows match. Avoid mountain ranges with thick, verdant forests on near and lee sides of the ridgeline.

- Avoid deserts touching forests. There should always be a buffer of grasslands between them. Fix on a case by case basis. That may be changing a single desert hex to a grassland or downgrading the single forest next to a big desert into a grassland.

How’s your map looking? I hope this helped you add some shine to your map and give a nice, organic look that also makes sense upon review. In the next section we’ll go over major watersheds and rivers. At the end of the next section you should know where the major watersheds and rivers of your world lay. You’ll also be knowledgeable about the rivers’ courses so you should have a solid foundation to decide your wetland types.

Hope you enjoyed this part of the Worldbuilding Process Posts series and found some useful information for your worldbuilding and mapping needs. If you like the content please share it online with the worldbuilders you know. If you would like to support me and the website I have some Pay-What-You-Want items you may like in the RRF DriveThruRPG Shop. Or, you can contribute to supporting the site directly by buying me a Ko-Fi. I don’t run advertising on the website or use affiliate links so your direct support is appreciated!

Pingback: World Building Rivers & Watersheds | Red Ragged Fiend